The eurozone, the ant and the grasshopper

Greek economist Yanis Varoufakis writes for Channel 4 News about why the euro crisis should not simply be seen through the prism of a famous Aesop fable.

Another summit, another “bailout” for Greece. Today’s Brussels’ agreement commits another mountain of euros to a cause that most think was lost some time ago. Europe seems to be caught up in an awful dilemma: cut Greece loose (possibly together with at least one of the other PIIGS – Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain – or keep throwing good money into a black hole.

Terrified by what an “amputation” might mean for the eurozone’s integrity, Europe’s paymasters (Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and Finland) are forcing the Greek government insincerely to accept impossible conditions in order to secure the fresh loans on the pretence that an unworkable fiscal consolidation programme can and will be implemented. In short, wholesale desperation has once again led Europe’s leaders to more bailouts and widespread deception.

Europe must at long last come to terms with the error of its ways. Perhaps a good start is the recognition that it has been using the wrong metaphor by which to make sense of what went wrong and how it ought to be fixed.

There are ants and there are grasshoppers in both Greece and in Germany, in the Netherlands and in Portugal, in Austria as well as in neighbouring Italy.

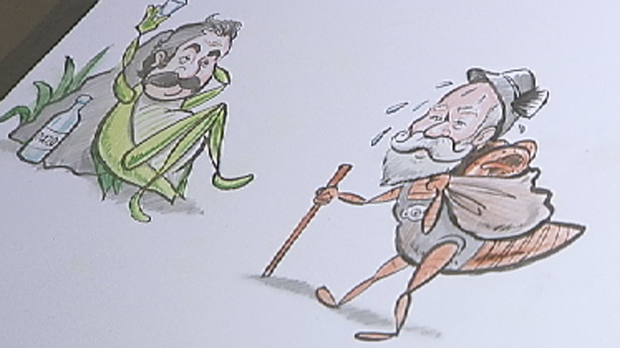

The Euro crisis is more often than not understood through the prism of Aesop’s venerable fable of the industrious northern ant that must, after the warm summer days have passed, bail out the profligate grasshopper.

Our video makes the point that there is something profoundly wrong with the way Aesop’s metaphor is applied to Europe’s current woes: neither the ants nor the grasshoppers are confined to one or more countries.

There are ants and there are grasshoppers in both Greece and in Germany, in the Netherlands and in Portugal, in Austria as well as in neighbouring Italy. And when we assume that all the ants are in the “North” and all the grasshoppers in the “South”, the remedies we introduce are toxic. Here is why:

Before the euro was established, a remarkable experiment took place simultaneously in Greece and in Germany. In Germany, government, employers and the trade unions agreed to try to restore German competitiveness (which had suffered due to the costs of reunification) by reducing German wages and, thus, squeezing German inflation below that of the European average. Meanwhile in Greece, to prepare the country for accession to the eurozone the authorities also squeezed real wages, taking advantage too of the influx of migrants into the country.

Read more: Is the eurozone on the brink?

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- subtitles off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

This is a modal window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

The German experiment worked a charm and kept working even after the euro was created. Real wages fell, unemployment was slashed, the gleaming factories produced more for less. Profits thus accumulated and caused money to become even cheaper, flooding the surrounding eurozone countries, including Greece.

Meanwhile in Greece, once inside the euro, the flood of cheap money from the outside, from Germany as well as from Wall Street, created bubbles. These bubbles allowed the Greek grasshoppers, and their political allies in government, to borrow from the German ones (the banks) as if there was no tomorrow.

Every time the Greek ants asked for some of the benefits of being in the euro, they were either paid off with cheapskate public sector jobs, paid for with borrowed money, or were told to go to the banks and borrow directly. Thus the Greek grasshoppers, in alliance with some German ones, got fatter while the Greek ants struggled to make ends meet.

Suddenly in 2008 Wall Street collapsed for reasons of its own. Europe’s banks were immediately hit, liquidity disappeared and, soon after, the Greek grasshoppers’ state went belly up, followed in quick succession by Ireland and Portugal.

Someone had to be blamed. Europe’s grasshoppers found it convenient to fall back on the scoundrel’s last refuge: nationalism. Suddenly a war of words was raging between Greeks and Germans, Northerners and Southerners hiding the terrible truth. The massive bailout funds were used to prop up the grasshoppers of both the North and the South. As for the ants, of both North and South, they were never bailed out.

Moral of the story

Aesop ended each of his fables with a moral. His Ant and Grasshopper was meant as a warning not only against the grasshopper’s sloth but also against the ant’s extreme parsimony.

Today there is another wrinkle that needs to be added to his moral: that when the ants and the grasshoppers are distributed across the division separating surplus from deficit nations within a badly designed monetary union, the stage is set for a depression that sets all against all in a vicious spiral from which only losers can emerge. No one can either be bailed out, or bail out, once this process begins.

Is there an alternative? In the video I allude to one such based on the idea of centrally managing (a) the supervision and recapitalisation of Europe’s banking systems, (b) a large portion of each eurozone state’s public debt, and (c) a Europe-wide investment-led Recovery program. This Modest Proposal, as we call it, can be gleaned here.

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- subtitles off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

This is a modal window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.